(As told to Alan Mitchell by Leon White)

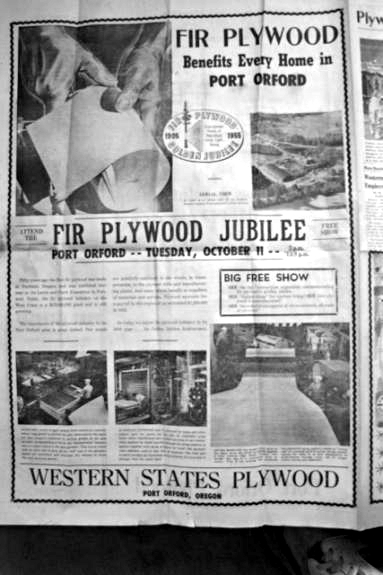

In 1949, there was a very large empty field bordering cold and clear Elk River. In 2021, the river still runs cold and clear and the land has returned to quiet pastureland. For 24 years though, this beautiful location was where Western States Plywood Cooperative prospered and reshaped the entire community of Port Orford.

Leon’s first job after High school began when he was hired to be one of a small Office Crew for the plywood mill along Elk River. It turned out to have been a very good fit. The job provided a paid vacation and Blue Cross Medical Insurance. Both of which were pretty much unheard of in Port Orford at that time. The work was year-round and life in the office was never boring. For instance there were days when tourists would show for a tour of the Mill. They would have come from all over and Leon would add their home states to a map he kept on the counter. It didn’t take long for three quarters of the 50 states to be represented.

His office mates were friendly and supportive. He has fond memories of Christmas time, when the office had Aplets and Cotlets to snack on, and the log inventory clerk (Hazel McKenzie) would bring in her home-made chocolates and other tasty Holiday treats to share. For many years, the Forester would bring small trees for staff to take home to use for their personal Christmas Tree.

Soon after being hired, Leon fondly remembers being in the room when one of his parent’s friends (Crawford Smith) praised him to Gene for having taken the job and then using those wages to support them – Gene (72 yrs) and Pearl (54 yrs) White.

Western States Plywood was a cooperative and had only been running for a couple of years. There had never been a plywood mill in the area. None of the locals knew quite what to make of the mill, but of course they had opinions. No-one expected it to last very long!

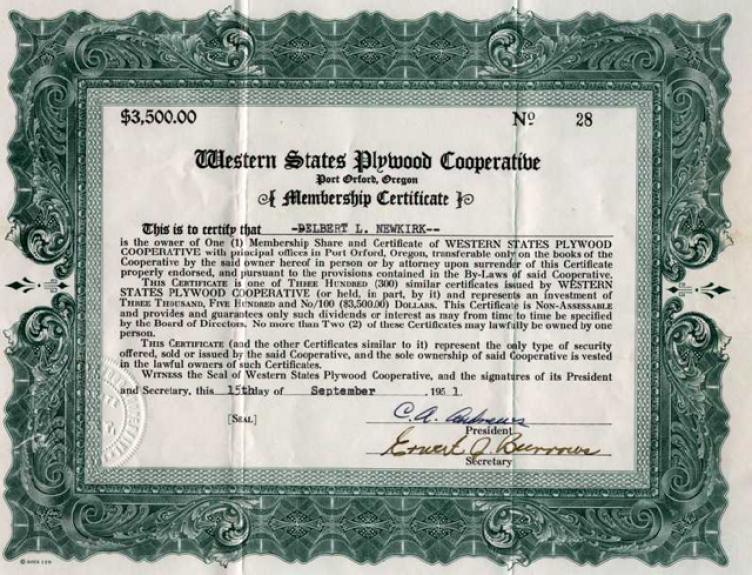

Many shareholders had previously worked at a plywood mill in McMinnville, Oregon. To work at the mill during its early years, you had to own a share. The first shares sold for $3500. (In 2022 dollars that would be approximately $39,000). Eventually workers were allowed to buy a share from a shareholder. When these were not cash transactions, the worker would make payments plus interest to the selling shareholder. The share would entitle a worker to a job, a better wage and other benefits. In a cooperative, all shareholders were equal in pay and voting rights. The plywood mill’s annual business meetings were held at the Sixes Grange Hall on a Saturday in January. Business reports were presented and seven people would be elected to be next year’s Board of Directors. There were years when entire boards would be voted out and replaced.

During the first few years, all of Management (The General Manager, Mill Superintendent, Timber Manager and Accountant) were shareholders. Larry Lindquist is remembered as being General Manager during Western State’s most productive and prosperous years.

The Accountant was in charge of the office. Each day, Management needed to know how productive the millworkers had been the previous day. Every morning, Leon processed the records of the Mill’s previous day’s production. Using that data, he calculated what the man hours and production per man hour per day had been at each of the mill’s machines during each of those three shifts. “The total of all the machines then was combined into one grand total for the entire mill for that day.” Leon’s report had to be completed by 11:30 am.

By the time Leon was hired, only two of the crew in the Office were shareholders. One of them would be the current Board’s President. The other shareholder working in the office was there because he had been injured while helping to build the Mill. The five other office workers were non-shareholders working at lower pay levels. Each position was paid a different rate according to their jobs.

Management employees always had the highest salaries in the business, with the Office crew having the lowest.

There were 12 Production Personnel (Bushelers) who did the job of veneer layup into 3, 5, or 7 ply plywood. They were paid by the number of panels made and often the highest paid employees. All employees could buy plywood at reduced prices. 2×4 studs made from peeler cores were available for purchase by employees. Shareholders paid discounted prices and more than a few became owner-builders, building their homes with Western States plywood and 2×4s .

Daily Commute Adventures

The mill was located 3 miles upriver from Hwy 101. There were three shifts at the Mill: Day – 7am to 3pm; Swing – 3pm to 11pm; and Graveyard – 11pm to 7am. Naturally this meant there was a steady stream of car and truck traffic coming and going along Elk River Road. Twice a day, Leon was one of those commuters. During those years, Leon had some close calls, a fender bender and, a ruined driver’s side door.

When he started at the Mill, Highway 101 was the only paved road in the area. Hwy 101 was located east of where it is today. It ran past the City Shop building at the base of Hensley Hill Road and around the curves at Silver Springs and Silver Butte. Elk River Road was graveled. There were plenty of potholes. After a good Winter storm, the biggest potholes became mud holes.

Leon recalled when one mud hole made for a memorable commute. It happened during a rainy afternoon. Ray Reinke and he had car pooled with Dorothy Baird. It was Dorothy’s car so naturally she was driving. Then she became stuck. After unsuccessfully trying to ‘rock’ the car to get them out of the mud, she had the good sense to ask Ray to try. Having grown up in North Dakota, Ray knew exactly what to do with the brake, gas and transmission to get them out. Once safely out of the mud, he pulled over so Dorothy could resume driving. Leon was very thankful because he had begun to worry that he and Ray might have had to step outside into deep mud to push the car out of the hole!

Elk River Road had been paved by the time of this close call:

“There was no safe place to pass. Heading to the mill one morning I was suddenly cut off by a car that had just barely passed me. I put my foot on the brake as hard as I could which caused me to fishtail onto the highway’s graveled shoulder. We did not make contact but it had been very close!”

LEON WHITE

The fender bender happened one morning when Leon was northbound on Hwy 101, turning onto Elk River Road. Suddenly, a southbound car also began to turn onto the same road, cutting into Leon’s lane as it did. Leon saw the car was slowing up, but it kept coming right at him. Leon remembers: “The potential was bad for both of us. I sped up to get out of its way. I almost made it, but the oncoming car put a big gash into my rear fender on the driver’s side. There was no damage to the viability of my car, it just looked bad. The other car’s bumper was not even damaged. I decided not to make an insurance claim on the other party as it was about time for me to get a new car anyway!”

Another near miss involved Winter conditions. He was heading east on Elk River Road down the hill before Paul Wagner’s open fields. The road there was pretty steep, with a couple of curves and a big drop off.

“Suddenly I was skidding and sliding on Black Ice. I had never driven much on ice and could not recall which way I should turn the steering wheel. I did remember I should not hit the brakes! Time seemed to stand still as I slid out of my lane, and spun around. Then I was stopped. I had been heading east towards the plywood mill and now found myself pointed west. I was thankful there had been no-one in that lane!”

LEON WHITE

His ruined driver’s side door happened in slow motion while entering the Plywood Mill’s parking lot. Leon remembers: “I saw an employee driving towards me at about 10 mph. I assumed he was awake and was about to turn to miss me. Well, he wasn’t and he didn’t. He had nodded off. He woke up just after he ran into me. It was the driver’s side. My door had to be replaced. As the accident was happening, I felt like I was seeing it in slow motion. I felt the bump and saw a cloud of little shards of glass flying in front of me like heavy snow.”

Fortunately, Carl Eskelson’s Car Repair was able to get a proper drivers’ side door from a junk yard for him a reasonable price.

Life (and Death) at The Mill

Employees had shareholder benefits. The ages of shareholders ranged between 30 to 60, with the most being over 45. Production non-shareholders ranged from 20 to 40. Blue Cross medical insurance was available to everyone at a very reasonable price. At Thanksgiving, all employees were given a gift certificate for a free turkey at McKay’s Market. Shareholders could buy discounted gasoline from the mill’s gas station at the edge of the parking lot.

Free scraps of firewood were available on the north side of the mill near the Wigwam Burner. For $20, Shareholder Don Mechals would deliver a truckload into town. The huge Teepee-shaped metal structure was used by the mill to safely burn the waste wood and bark it could not find a market for. Some mills would install a heat exchanger inside their wigwam to make steam for the plywood manufacturing process. Today’s term for that is ‘Co-Generation’.

Work at the mill, while noisy, was not particularly dangerous. The Mill had a nurse on site to care for minor issues like headaches, cuts, and wood splinters. Dee Hansohn and Lucille Estabrook were the Mill’s two nurses. There were occasional on-the-job injuries, but rarely any deaths on site. Of course, the workers’ lifestyle involved a lot of smoking and drinking. In the beginning, when an employee became sick and died, employ-ees would take up a collection for the Mill to give to the spouse or family of that employee. After a few attempts at this, the reality was the amounts donated amounted to popularity contests. The Board then established a fund that all could pay into. That way all employees could be assured their ‘Heirs’ would receive something in the event a tragedy befalling them or their families.

One instance of a tragedy was when three shareholders each lost a son on the same day. The boys were only about 19 and worked together at the mill. While riding together on their motorcycles down a hill on Hwy 101 near Yachats, a truck suddenly pulled out in front of them. All three boys died. In those days, motorcyclists were not required to wear helmets. Another time an employee and his young family were in a head-on collision on Elk River Road. One or more of his children died. In those days, seat belts were not required. Another death involved a shareholder on his lunch break. He was at the Port Orford Dock enjoying his homemade lunch when he accidentally swallowed a chicken bone. The only on-site death was when an employee fell into an active Log Pond and drowned. The worst accident Leon recalled was when an employee working with the Mill’s big saw, accidentally cut off most of an arm. Leon was amazed that when medical help arrived, that worker was able to be walked out to the ambulance.

During its 25 years in operation, there was only one prolonged mill shutdown. That shutdown lasted 3 months and towards the end, an employee sadly hung himself in his garage.

The Columbus Day Storm of 1962

Like the rest of Oregon, Western States had no warning. After it was over, the highest winds ever recorded in Western Oregon and Northwestern California had torn through our Mill.

Port Orford is an oceanside, weather-exposed community. Cape Blanco is close by and annually records extreme winds and rains all year long. When the windspeed is 100 mph at Cape Blanco, Port Orford will be seeing 85-90 mph wind speeds.

“When the wind and rain began around 9am during the morning of a regular work day for me, it felt like nothing unusual. By 10am we could feel the storm was becoming a lot windier. Then by 11am it was obvious this was going to be one of our really Big Wind Storms. By 11:30am we were taking one phone call after another from frantic wives at home. “Tell my husband to come home now! We have shingles blowing off our roof, and the storm is getting worse!”

LEON WHITE

Around noon, a millworker came to the office and told the Manager and Superintendent: “The wigwam burner had blown over!” The burner was lying on its side, on the north side of the mill. Then another report came in that a big door on the east side of the mill building had been completely torn off and was being violently blown about in the open area next to the mill. By 1:00pm, Management decided to shut the Mill down and told everyone to go home to deal with what was happening.

Leon recalled that while driving home that afternoon from the Mill on Elk River Road, you could see lots of downed power lines and poles, flattened fences and small trees. Just before the connection to Hwy 101, entire trees were blocking Elk River Road. They were directed to take a one-way dirt road bypass through a pasture to connect with 101. About 3 miles north of town, trees had fallen across Hwy 101. Traffic was at a standstill. Everyone waited patiently for loggers to arrive with chainsaws to free us. Fortunately, there had been a couple of crews who had been working that day on jobs way up the Elk River. “Before the loggers arrived, I got out of my car to see what was going on. I was surprised to feel a slight ‘Salty’ moisture in the air.”

After the trees were cleared from 101, Leon continued on to Port Orford and home. Along the way he saw a lot of storm damage and began to worry even more about what might have happened to his home, exposed as it was overlooking the harbor.

“Relief! My damage was small. Later I learned that a woman schoolbus driver was killed near Ophir when a tree fell on her bus. I believe there was another local person killed by the storm. I saw houses and buildings in Port Orford that had been severely damaged. Two near me had to be demolished.”

LEON WHITE

One demolished building was the Herzig Shoe store next to Susie White’s commercial building (The old Western Hotel.) The other was a house up by the Castaway. When it was all over, historians had determined it had been the worst Oregon Coast Winter wind and rain event ever recorded.

Women working at WSP

Viola Cuatt was a shareholder’s wife. She headed the Western States Plywood Women’s Auxiliary. Port Orford usually had one doctor, but had no doctors when the shareholders arrived. Viola helped form the Port Orford Ambulance Association, then obtained an old ambulance for the Women’s Auxiliary to operate. The Women’s Auxiliary then reached out and brought in two doctors for the Community. Another thing to remember about Viola is that she was the main force in the Curry County Historical Society that headed up the preservation of the Hughes House and its ranch. Once preserved, it eventually became part of the Cape Blanco State Park.

It was not until 1970 that women were allowed to become shareholders and work at the Mill. They were allowed to have some of the ‘good’ jobs and have voting rights at Annual Meetings. Microwave ovens had not been invented yet, but with the Board’s approval one of the shareholders had a machine installed to heat up small cans of pre-cooked food like Chef Boyardee. Hot lunches then became very popular. Around the same time, a dispenser of Coca Cola and other soft drinks was installed as well.

Politically, a lot of the shareholders had lived through the Great Depression of the 1930s. In the process, they had become solidly President Franklin Delano Roosevelt supporters.

The Western Staters

The “Western Staters” brought a lot of changes to the community. When Shareholders began arriving in Port Orford, they found few modern homes available for purchase, so they started building their own. One subdivision in particular, the Geer Tract, became popular with Shareholders. The developer’s name was Herb Geer. Many Shareholders also built their homes upriver from the Mill along Elk River.

Pacific High School needed to be built in northern Curry to accommodate the additional children of Western States Plywood Mill’s shareholders and employees. A football field was added in the ‘60s when the men wanted their sons to be able to play.

Shareholders’ children were given preference for all seasonal jobs at the Mill. There were quite a few who were able to pay for their College Education this way.

City of Port Orford

During the ‘50s, before the Western Staters arrived, the City’s population was about 700. The City of Port Orford got a sewer system in the 1960s which allowed even more homes to be built to accommodate all the new people. That influx of people associated with the wood products industry in the ‘70s eventually tripled the City’s population, to about 2300.

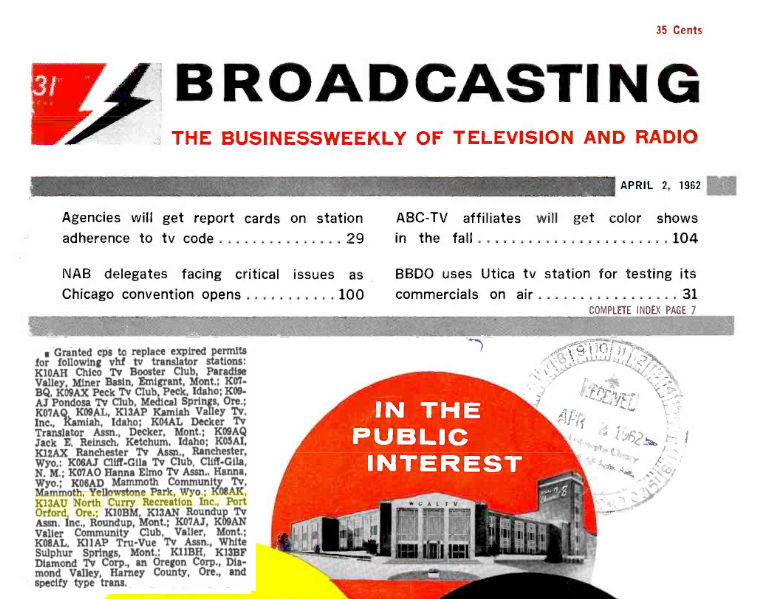

Back in the mid-1950’s, television was one weak channel, whose picture came straight across 150 miles of open ocean from Eureka, California. One did not pick it up with rabbit ears; nor did it stay very long after one had it in the living room, via an expansive antenna on the roof or in the nearby tree” (Mabel Edwards, wife of Bill Edwards, a Shareholder). A non-profit corporation was formed to install and maintain an antenna and electronic equipment on a hill overlooking Port Orford to pick up distant TV signals, amplify and rebroadcast them. The corporation was originally named North Curry Recreation, renamed North Curry Translators in 1978, then dissolved in 1998.

Active civic groups like the Lions and Rotary Clubs, the Back Acres and Sunset Garden Clubs were formed. During the ‘70s, the Lions Club went on to help establish the Buffington City Park.

A lot of growth happened in the early 1960’s when Oregon’s forests became more sought after by the wood products industry. The reason Oregon’s coastal forests were being opened up at that time is that huge lumber and plywood corporations like Georgia Pacific and Weyerhauser had logged off much of the timber in the state of Washington. They needed more timber to keep going and began moving in on Oregon.

Without Federal help, none of Oregon’s small lumber and plywood mills could pay the high bids for logs that the GPs & Weyerhausers could. Tiny Western States Plywood Cooperative was only able to exist as long as it did because nearby Federal forests were being opened up to timber sales.

The Federal Government required that on smaller tracts only companies with fewer than 200 employees could bid. For as long as local timber was available, Western States with its 120 employees was able to prosper.

By the late ‘60s though, that was not enough. An opportunity in Alaska to purchase a lot of timber a low price became available. Western States entered into a tentative agreement with the Alaska owners, but due to numerous problems the deal was delayed and never completed. In the process, Western States had spent quite a bit of its working capital before it had to give it up with no logs to show for it.

The price the Mill got for its plywood was always subject to the national market. Western States would make a good profit some years and then have big losses other years. By 1970, a combination of the above issues led banks to stop lending to the Mill. That was the reason for the end in 1975. When the end came, the Mill phased down its production and after a couple of weeks it was all over.

Life after Western States Plywood

We could no longer compete with the big timber companies. Western States Plywood closed in October of 1974 after about 24 years. The closing was a very sad occurrence for me and the 200 families the mill supported in Port Orford. I greatly enjoyed my years with WSP. The cooperative mill had been the heart of Port Orford.

JIM ROGErS, A BRIEF HISTORY OF thE gRASSY KNOB WILDERNESS

A factor people were not taking into account was that many of the shareholders were at the age of retirement and owned their homes. There were a few who opened small businesses like a gift shop, restaurants or a variety store. It was true that the population dropped, but never did “Grass grow in the streets”!

“During the years before it finally closed down, it was believed by many that once the Mill was gone, grass would grow in the streets of Port Orford. DID NOT HAPPEN!”

LEON WHItE

Postscript: After the Mill closed and liquidated its equipment, a small company (Phoenix Western) bought out the shareholders for a token amount of money and started using the Mill to make laminated wood ceiling tiles. Within a matter of months that new little company had failed, then soon after that another one of Port Orford’s fires occurred and the Mill burned up one night.

Priscilla Montgomery Lang

Another great story!! I went to work at the mill in September 1968! It was a lot of fun, except for the slivers I got! Mostly in my arms!

Carren Copeland

Great information I live in Geer tract love Port Orford history

Cody wilson

I was born right next to that mill. Grew up playing on the old burner. I was there the winter the storm blew it over. Some of my best childhood memories take place at that mill

William Masters

I found this article to be a great read and very informative.

I always thought Pacific High School was put where it was. Because it was just about middle between Port Orford and Langlois.

I also heard the land was donated by the Quigley family in exchange for a permanent job at the school. Where he became the Janitor.

Paula Mensing

Thank you for all of the great information!

My dad and uncles were working at the mill on Columbus Day. I remember them telling stories of the shack (for the log pond?) blowing over and whoever was out there had to crawl along the catwalk to get back inside. They also told of how they had to saw their way home.

Michele Leonard

What a wonderful historical account of important times past. Loved getting a glimpse of another era. Thank you for taking time to tell a story for all to learn by.

Dennis Dougherty

I work there two summers 1969-70 while attending OSU and OCE. I have a small photo tablet of the mill being constructed that my Dad , Charles Dougherty was given in 1951. I was able to work on the green & dry chain, clipper and mill pond. Put me through school. I felt fortunate to be able to work there. I’d send pictures of the construction if I knew how😊

admin

Hi Dennis — thanks so much for your generous contribution to our website. Your father’s photos have been scanned, retouched and added to the Port Orford Historical Photos Project here: https://blog.portorfordhistoricalphotos.org/western-states-plywood-in-1951/

Tom Christopher

My family moved there from North Carolina when a couple of my uncles and their families moved there for better paying jobs. I don’t know how they heard of Port Orford while living in North Carolina but someone must have told them of the good paying jobs at Western States Plywood Mill. For me it was a great no it was the place to grow up. When the mill was running it seemed like a different type of people lived in the area than now and I miss the people of yore. Growing up during the time the mill was running was awesome. Port Orford had 5 gas stations, 3 grocery store, a meat market and yes they processed your freshly killed Deer or Elk, movie theatre where the teenagers got smacked by the yard stick, walking from Myrtle Lane with friends at age 9 or so going fishing off the dock or the surrounding rocks with no adult supervision and not to mention trout fishing in Garrision Lake, going into the forest camping or fishing for Salmon on one of the rivers, cruising in Port Orford oh the list could go on. It really was the best of times for Port Orford, Langlois and the surrounding area.

Sue McKinney

My Dad worked at the mill from 52 to 74. He was the head lathe operator.

Funny story about him. He started losing his hearing and decide he needed to see the DR. about it. Well the Dr. examined him and said: “Kight you don’t need hearing aids you need the wax cleaned out of your ears.” After that Dad started wearing plugs in his ears when he ran the lathe…I grew up in P.O. some of the best times of my life. I still call it home even after being gone for 60 yrs.

mike hardy

I remember in the mid sixty`s going to work with my father Lew Hardy for the graveyard shift on the weekends and loading the boilers with hog fuel (sawdust). My mother Shirley,(that just passed and went home to the lord 3/24/24) made us a great lunch! Port Orford and Western States Plywood, Pacific H.S. and places like Battle Rock, Sixes River, Elk River, Paradise Point, and all the great places were for me and my family, a great place to grow up with great friends.